Setsubun 節分 is a Japanese celebration best known for the traditional scattering of beans, a custom particularly popular among Japanese children – the older boys or other members of the family wear oni 鬼 (ogre, devil) masks, and the younger ones chase them around, throwing fuku mame 福豆 – lucky beans – and shouting the motto “oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi!” 鬼は外、福はうち – meaning “devils out, fortune in!”.

While this is the custom that first comes to mind talking about setsubun, it is not the only one associated with this very ancient celebration. Let’s discover some of the others together, but first, what are the origins of setsubun?

The year’s milestones

The name setsubun literally means “seasonal division” and refers to the day before the start of a new season. Since there are four distinct seasons in Japan, the setsubun happens four times, on the days preceding the first day of spring (risshun 立春), summer (rikka 立夏), autumn (risshū 立秋) and winter (rittō 立冬).

In the past, the same word was commonly used in reference to all four “seasonal divisions,” but today, by setsubun, people generally mean the day before the beginning of spring – risshun. Why the prevalence of this season? The reason is in the connection between the “spring setsubun” and the Lunar New Year.

As spring was considered the start of a New Year, and although Japan officially moved to the solar calendar in the 19th Century, the day before spring is still traditionally seen as a period of renovation in which well-wishing rituals are in order to ensure a good New Year.

Traditional Japanese culture gives great importance to periodic purification rituals. Many of these rituals coincide with popular festivals, and serve as milestones of the passing of the year. See the article about the major Japanese festivals and the foods they are typically associated with.

Scattering beans, chasing away devils

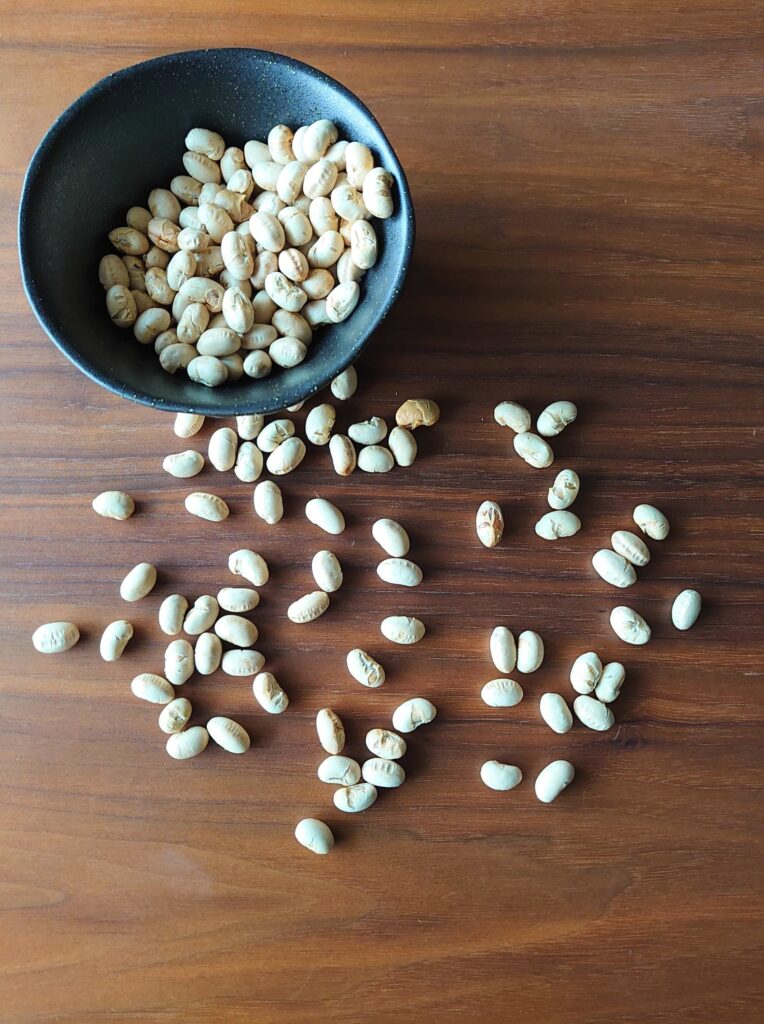

The tradition of scattering lucky beans – fukumame, roasted soybeans- is said to come from the similarity of the word for “bean” in Japanese (mame 豆) and a phrase alluding to “smashing the devils’ eyes” – pronounced as mame too, but written with different characters: 魔目.

Throwing things to smash devils’ eyes and exorcise evil was necessary to bring about a good year; back in ancient times, when Japan was still following the Lunar Calendar, this kind of exorcism was performed on the occasion of the Lunar New Year in a rite called oni yarai 鬼やらい, which is said to be the origin of the scattering of beans tradition of setsubun.

Another custom of setsubun, intended to bring good fortune, is the one of eating one fukumame for each year of one’s age, plus one. This practice too, was a well-wishing ritual related to the Lunar New Year, with the significance of welcoming another year and praying for it to be free of harm.

Other foods connected with setsubun

Another food item that was connected with the purification rites of the Lunar New Year, and now with setsubun, are sardines – iwashi 鰯 in Japanese. Their “pungent” smell is considered to be disliked by the oni, thus the tradition of grilling them on the evening of the setsubun.

It’s not clear why the smell of the sardines, in particular, would be capable of warding off evil spirits, but as sardines fished in the wintertime are fattier, which means tastier, it might still be worth a shot to grill some!

Another custom of the setsubun that involves sardines is the one of hanging lucky charms made with the heads and bones of the fish, together with holly leaves, on one’s house entrance; the fishbones would be dangerous to the oni’s eyes, already hurt by the beans, and thus would ward them off.

A more recent tradition, which is said to have started in the Kansai region of western Japan, is that of eating a propitiatory sushi roll called ehōmaki 恵方巻. The roll may contain different ingredients, typically seven, as there are seven lucky gods in Japanese tradition.

The ehōmaki, which literally means the “roll of the lucky direction”, has to be eaten while staying completely silent, facing the direction said to be auspicious for that year, the one from where the “god of the New Year” – toshitokujin歳徳神 – will visit from. Toshitokuji, also known as Toshigami-sama 年神様, is the divinity celebrated on New Year, so it’s easy to see another connection between setsubun and the Lunar New Year.

A more “profane” explanation, on the other hand, is that this particular custom wasn’t really so common and that its spread is due to a “marketing campaign” promoted by sushi sellers; what is for sure is that the custom of eating ehōmaki, most probably started in the Kansai area, had spread to the rest of Japan by the early 2000s.

Deeply connected with the old Lunar Calendar New Year’s traditions, setsubun is an occasion too to start fresh and bring in good luck for the rest of the Year! It’s common to have a false start of the year, so why not eat some fukumame, grill some sardines, and take the setsubun as a second chance to start with one’s New Year’s resolutions?